Recent local strike activity is unusual though not unprecedented

Recent local strike activity is unusual though not unprecedented

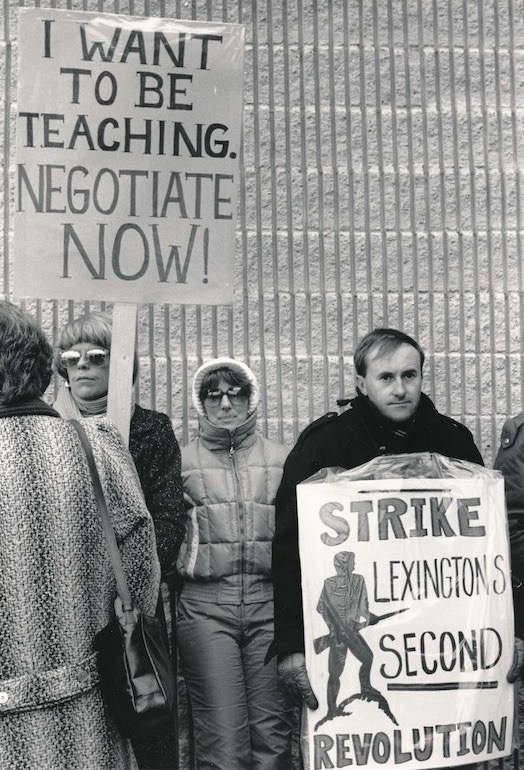

Educator strikes in Beverly, Gloucester and Marblehead in November bring the total number of strikes by MTA locals since 2019 to 12, an unusually high number for recent times, though reminiscent of the 1980s. Why now? Have the reasons for striking changed over the decades?

The MTA History Project has been collecting information on past strikes by MTA locals to help answer those questions. We will share that information through an interactive, web-based timeline in the coming months. Here is a preview of some of the information we have collected.

- There have been 55 strikes by MTA locals over the past 55 years, distributed unevenly in ebbs and flows. The peak year was 1987, when 10 locals went on strike.

- Strike activity was heavy from 1980 through 1995, with 33 strikes in 16 years. Much of this period coincided with a sharp drop in school funding as a result of Proposition 2½, the property tax cutting measure approved by voters in 1980. That approval led to widespread layoffs, school closures and downward pressure on salaries.

- Strike activity was very low from 1996 to 2019. There were only three strikes in that 23-year-period. One factor was that state funding for public schools increased significantly after two MTA-backed measures — a lawsuit and a funding bill — yielded results in 1993. In response to a lawsuit by the Council for Fair School Finance, the state’s highest court ruled that year that the Legislature wasn’t meeting its constitutional obligation to adequately fund public education. Shortly after the ruling, the Legislature passed the Education Reform Act, an omnibus law that significantly increased state funding for public education, especially for low-income districts.

- Strikes are usually, at least in part, about salaries and benefits, but often also about language pertaining to terms and conditions of employment, such as winning preparation periods, honoring seniority in reductions in force and implementing more productive evaluation systems. For example, following the Somerville strike of 1972, elementary teachers finally secured preparation time, though it was just for one period, on one day a month.

- MTA members have long made the case that student learning conditions are educator working conditions and therefore subject to bargaining, leading members to seek limits on class sizes and more resources for students. In a strike in Attleboro in 1986, for example, the members demanded new and better textbooks, noting that one still in use predicted that “man would land on the moon one day.” The Apollo 11 moon landing had occurred 17 years earlier. Student learning conditions are still a top concern. Recent strikes have focused on the need for more staff to address students’ increased social and emotional needs.

- A feature of recent strikes is that student living conditions are also on the table, a trend called “bargaining for the common good.” An example of this is the Malden Education Association strike of 2022, when the MEA pressed the district to commit to a plan to address housing insecurity.

- Another focus of recent strikes, that was rarely present in earlier decades, has been boosting the pay and benefits of paraeducators and other Education Support Professionals. These are often characterized as “living wage” campaigns. In the early years, ESPs were not always unionized; if they were, they were not always affiliated with the MTA. There has been a growing awareness of the important role they play in education, especially as students’ social, emotional and academic needs have grown.

- An additional, prominent issue has been to secure paid family and medical leave for educational staff. That leave is now guaranteed for most private-sector employees in Massachusetts, but not for municipal employees, unless they fight for it.

While funding issues have a lot to do with strikes, so do public attitudes about unions. The recent surge in strikes by MTA locals began in 2019. It followed shortly after the Red for Ed movement that began in West Virginia in 2018. That movement was embraced by many educators and union leaders across the country, including in Massachusetts.

Barry Davis, president of the Haverhill Education Association, underscored that point in a speech he made in support of the recent North Shore strikes. He is quoted in The Boston Globe saying, “It is time that the elected officials of Massachusetts realized that these are not individual moments, that this is a movement.”

Nationally, the public may be more accepting of strikes, though acceptance is far from universal. While strike activity has increased across the country in recent years, Gallup polls indicate that public opinion in support of unions has also increased during that period.

That said, striking is never undertaken lightly by local unions. The emotional and financial costs are high. Many picket signs at local strikes in the past read, “I’d rather be teaching.” Over the period in which 55 MTA locals have gone on strike, thousands of contracts have been settled without any work stoppages. Members say they only strike when they feel they have no other choice. As Linda Callaghan put it during the Educators Association of Freetown and Lakeville strike in 1989, “Sometimes you just have to stand up for what you believe in.”

More information and photographs from strikes from 1969 to the present will be available on the interactive timeline in early 2025.