Educators welcome all students

Educators welcome all students

Laura Barrett,

Communications Specialist

Immigrant and ethnic minority students — and others who belong to groups disparaged by President Donald Trump — have been feeling more vulnerable and anxious than usual since the 2016 election. MTA members are fighting back to make sure all students feel safe and welcome in our schools.

Pablo Frias-Mota, an adjustment counselor in Worcester, said there were two early flashpoints for immigrant students — first when Trump was elected and then right after his inauguration.

"When he was elected, many students were scared and some didn’t come to school the next day," Frias-Mota said. "At first there was some bullying of kids who were immigrants, but we took action right away to stop that. I tell students that we all came from someplace else. Even Native Americans. Even Donald Trump. Our superintendent sent a letter home explaining that the schools will educate all students and will never ask their legal status." Despite reassurances, students whose families lack documentation face real risks.

"In school we provide students with breakfast because we know that the brain doesn’t work well if they have empty stomachs," Frias-Mota said. "How are children supposed to learn if they are worried that their parents can be deported at any time?"

Lauren Harrison, an elementary school English as a Second Language teacher in Watertown, said that election time was stressful, even for young students.

"One kindergartner came to me and said, ‘I hate Donald Trump,’" Harrison said. "That student had been having nightmares that Trump was chasing her and her family and destroying her home."

Watertown educators Heidi Baildon, Lauren Harrison and Nyssa Patten joined the huge crowd on Boston Common to #DefendDACA #HereToStay pic.twitter.com/Po5LK1VZLj

— Mass Teachers Assn (@massteacher) September 16, 2017

The stress has also been significant for students participating in the Obama-era Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program. The DACA program provides temporary legal status to some immigrants who were brought to the U.S. when they were young.

Saul Ramos, a paraeducator in Worcester, was inspired to act when Trump announced on Sept. 5 that he was ending DACA in six months.

"A government history teacher was explaining DACA when one of the students blurted out, ‘I’m a DACA recipient,’" said Ramos. "All the other students were surprised. ‘What do you mean?’ they asked. ‘You only speak English.’

"The student explained that he was brought to the U.S. from Brazil when he was 2 years old. He has never been back and doesn’t speak the language. The other kids were sympathetic and upset that he might be sent back to a country where he has no family or connections."

Responses by MTA members to the trauma include classroom discussions, political action and family outreach programs.

Classroom discussions

After the student announced he was a DACA recipient, Ramos worked with the Educational Association of Worcester and the MTA to produce "I Support DACA" stickers for staff and students to wear on Oct. 5, the deadline to apply for a DACA extension.

"In my school the kids were all over the stickers," said Ramos, who is the NEA Education Support Professional of the Year. "They wanted to show support for their friends." The stickers also led to discussions as people asked what DACA was and why the wearer supported it.

Nyssa Patten, a high school ESL teacher in Watertown, said that discussing big issues is important for making students feel supported.

"After the election and the Muslim travel ban, I brought in school resource officers to explain that, at least in Watertown, police would not be knocking on doors to take people away," said Patten.

Despite precautions, some students still faced hostility.

"There was an incident in the library, where they were projecting the inauguration," Patten said. "We also happened to have a shelter-in-place order at the time so students couldn’t leave. Some students started chanting, ‘Build the wall! Send them home!’"

Patten talked about the incident with her students. She believes that open discussion can increase understanding and reduce prejudice.

One of her colleagues, Heidi Baildon, a middle school ESL teacher, has incorporated lessons from Facing History and Ourselves, a nonprofit educational and professional development organization, into her curriculum. One unit included reading a story about a bear that hibernates and wakes up to find that a factory has been built on top of him. Suddenly, he is being identified as a worker and no longer as a bear. This fostered a discussion about identity.

"It's so bad, even the introverts are marching."

Watertown ESL teacher Lauren Harrison

Baildon also makes sure that her students have access to positive images from varied cultures, including those in a graphic novel with Mexican superheroes to show that heroes aren’t all white English-speaking males.

Political action

"Public education is for all students. It is one of the only places left in America that will still take your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to be free. And it will provide those masses with the freedom and opportunity that come from a quality education. Do you know why, Betsy? Because we will teach them all!"

Rockland teacher Graciela Mohamedi at a Betsy DeVos protest rally in Cambridge on September 28

Baildon, Patten and Harrison were among the MTA members who attended a Sept. 16 rally in Boston in support of DACA.

Patten described herself as an introvert, noting that she had never been to a protest march before Trump was elected.

"I talk to my students a lot about acting on their beliefs," Patten said. "Up until now my way of participating has been teaching and telling others what to do. But that’s no longer enough. I have to do something. I’ve shown them pictures of me marching. They are really touched because they know I’m marching for them."

Harrison added with a laugh, "It’s so bad, even the introverts are marching."

Cheryl Olson, a math teacher from Gloucester, also felt compelled to attend. "Gloucester was built on waves of immigrants," she said. "The more diversity in the world, the more interesting it is.

"I cannot sit and be silent," Olson continued. "That’s what a lot of people did in Nazi Germany. Even though you get battle fatigue, you have to be out there. You have to speak out if you want a voice."

Family and community outreach

In response to high dropout rates among Latino students, Waltham High School hired Mary Jo Rendón in 2012 as the school’s dropout prevention specialist. As a result, Waltham has several programs in place that help students and families navigate the system in the Trump era.

"I’m a cultural broker in many cases," said Rendón, who immigrated to the U.S. from Guatemala when she was a child.

She helped launch the Waltham High School Newcomers Academy for recent immigrants who need extra support. "Some of these students are illiterate in their own languages, so it is especially challenging for them to learn to read in English," Rendón said.

She also has started a Family and Community Engagement program to create a welcoming climate at the high school for immigrant families. One strategy has been to organize monthly Saturday workshops at which educators and guidance counselors describe programs and resources offered at the high school.

"It’s taken about five years to build collaboration with families," Rendón said. "At first I had no parents, then one, and then three." To get more families there, she spent hours on the phone and met them in coffee shops on their own turf. Now she has about 15 parents and guardians, mostly mothers, who come every month. She is training them to help her bring in new families.

Rendón also runs a Community Café, a one-hour monthly gathering on a weekday morning to get parents, mainly fathers, more involved in the school community. "Last year the conversations focused on the climate in the nation and racism and about how we can support our students more," she said.

Based on models in California, Boston and Springfield, she also has established a Parent-Teacher Home Visit program. About 20 teachers volunteered to take part in a two-day training in August. They have begun visiting students’ homes this fall.

Electrical technology teacher Victor Vaitkunas explained why he is participating.

"I had such great teachers through the years, from elementary school on through high school," he said. "I wanted to pass that on and make a difference in kids’ lives."

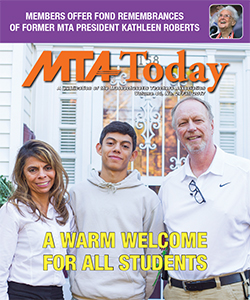

On Oct. 19, Vaitkunas and Rendón met at the home of junior Michael DeGloria, where they were greeted warmly by DeGloria’s mother, Johana Rodríguez. Rodríguez immigrated to the U.S. from Honduras when she was young, while DeGloria was born here. He was selected for the home visit program because he had found a program that he loved and a skill that he excelled at, and the staff wanted to keep him heading in a positive direction.

Vaitkunas said that his short-term goal is for Michael to continue to do well in both his written and vocational assignments.

"For the long-term goals," Vaitkunas said to DeGloria, "when you graduate from high school, you will have to choose whether to go to college, work in a trade, or enter the military."

Asked about his own goals, DeGloria told his teacher that he really wants to be an electrician. "I don’t like sitting still in class," he said. "I like hands-on projects. I like walking around in electrical class and looking at what I did and saying, ‘Did I just do that?’ I want more challenging projects to work on so I can learn it all."

Vaitkunas said that if DeGloria keeps up the good work, he’ll be one of two students recommended by Waltham High School for a five-year union apprenticeship program. He said that starting pay for an apprentice averages about $19 an hour; pay for a licensed electrician can be about $50 an hour.

Rodríguez was asked about her goals for her son.

Clearly emotional, she told Vaitkunas, "Most of all, I want him to be happy and to love what he is doing. I thank you for your commitment to my kid. I want to send a message to all teachers that everyone needs at least one person who believes in him to make it in this world. I thank God you were put in his path. You have made a big difference in Michael’s life."

This story initially appeared in the Fall 2017 edition of MTA Today.